A new El Niño is now brewing. NASA satellite pictures indicate this year’s could be even bigger than the 1997-1998 one, the strongest on record. So what is El Niño?

Spanish for “little boy”, El Niño was so named by Peruvian fishermen in the 1600s in honour of the Christ child. They observed that periodically around Christmastime, Pacific waters grew warmer and fish vanished, migrating to cooler waters.

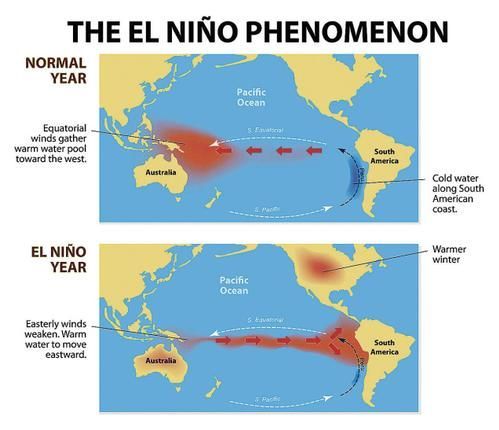

Unlike hurricanes, El Niño is not an individual weather event, it is a climate pattern. In non-Niño years trade winds, which blow east to west, push warm equatorial water into the western Pacific, allowing cold water from the deep ocean to well up in the eastern Pacific. During a Niño, those winds slacken. The warm water that is normally pushed westward pools right across the Pacific Ocean. Water temperature increases, and increased heat and moisture rise into the atmosphere, altering wind and storm patterns.

If ocean-surface temperatures are between 0.5 to 1°C above average during a three-month window, America’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a federal agency, deems it a Niño. The current one could produce temperatures 2°C higher than average, or more.

A Niño generally produces heavy rains, higher temperatures and cyclones in parts of South America and east Africa. South-East Asia and Australia could see drier weather than usual or drought. Some countries are already feeling its impact. Thailand is rationing water. The Peruvian government has declared a state of emergency because of heavy rain and mudslides. This Niño is partly to blame for drought in parts of Central America, Indonesia, the Philippines and Australia. The Panama Canal’s water levels are so low that officials there have limited traffic.

Globally, its effects could be devastating. Some countries could see inflation, according to a recent University of Cambridge paper, thanks to disruptions to trade and harvests. Agricultural and economic havoc could fuel political conflict. Indeed, Columbia University’s Earth Institute found that Niños double the risk of civil wars across 90 tropical countries. Not all its effects are bad. One study shows that a Niño may reduce the number of tornadoes in the Midwest. It may also suppress hurricanes from forming in the Atlantic Ocean. Many in California, which is in its fourth year of a drought, are hoping the current Niño may shorten their dry spell. America’s Northeast may also see a milder winter.

The current Niño may prove a doozy. It could be long-lasting: on August 13th, NOAA forecasters said there is a 90% chance this Niño will continue through the winter months, and an 85% chance (up from 80% in July) that it will last into early spring next year. Some scientists are using headline grabbing language, such as “Godzilla El Niño” and “Bruce Lee El Niño” to indicate how powerful it could be. A powerful Niño could also affect the climate-change debate. A Niño’s rapid release of stored heat produces sudden global warming. It is, many climatologists believe, no coincidence that a recent apparent pause in global warming coincides with the quiet period since the last big Niño. Godzilla El Niño, by contrast, could make 2015 the hottest year on record, by a long shot.

Taken from The Economist