EUROCLIMA+ and Women on the Move presented research on the effects of mobility and the health contingency with a gender perspective.

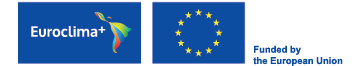

Mexico City, August 25, 2020. - The health contingency caused by COVID-19 and the measures taken to prevent its spread highlighted the social inequalities towards historically vulnerable groups that already existed before the pandemic. What long-term actions can be taken to counteract these effects?

The EUROCLIMA+ programme promotes initiatives and knowledge for sustainable development that integrate factors such as social inequality and the gender perspective in an intersectional manner. This is why, together with the organisation Mujeres en Movimiento (Women on the Move), it developed the virtual seminar "How do Latin American women move about during the pandemic?

During this meeting, recent results from two studies were presented on how women's mobility has been affected during health contingency in Latin America, and subsequently the impact that the region's cities have had on mobility from a gender perspective was analysed. The panellists for the conversation were Laura Pérez, from Ciudades del Futuro (Cities of the Future); Georgina Sticco, from GROW; and Alejandra Conconi, from GROW. Valentina Montoya from the Transport Gender Lab moderated the discussion. It was held on August 20th and was attended by 158 people.

Effects of COVID-19 on women's mobility in Mexico

During the first presentation, Laura Pérez presented a study carried out by Ciudades del Futuro (Cities of the Future), a programme that works in Mexican cities to improve sustainable mobility, especially for women and girls. The research found some recurrent effects in cities around the world:

- Increases in unemployment and growth of the precarious informal sector, which disproportionately affects women

- Increased vulnerability of essential service personnel, mainly women in activities related to health, cleaning, and food.

- An increase in the burden of domestic work, which predominantly affects women, as they are delegated the responsibility for this activity.

- An increase in the rate of domestic violence against women

- Increased risk of contagion for adults and people with chronic or immunodeficiency diseases, which mainly affects those living in poverty.

It should be noted that women have had less access to development and services even before the pandemic, a condition that has become more pronounced in recent months. While mobility services allow them to carry out their activities and access opportunities, city planning has not taken their needs into account.

"We live in cities planned and built based on the mobility of men. Our cities were built with this sexual division of labour in mind where men work and women stay at home. They haven't really evolved with society, and women's mobility remains invisible," said Laura.

With the arrival of the pandemic, responses to COVID-19 regarding mobility were generated quickly and reactively, transforming lives and limiting people's daily movement. According to the study, these measures do not essentially consider the way women move, which affects their experience as users. This mainly affects the following aspects:

- A limited ability to move due to reduced income, which increases the transport cost burden. This mainly affects women living on the periphery.

- An increase in transport costs by having to find alternative routes in the face of limited transport services.

- Informal employment. In Mexico, 23% of economically active women are in the informal sector.

- Difficulties in carrying out everyday activities and work-related tasks.

- Modification of routes for shopping or access to health centres is disrupted.

- An increase in women's perception of insecurity in moving around on public transport and in the streets due to the reduced flow of people and the closure of establishments in public space.

- Faced with the fear of violence and now contagion, women have changed their travel behaviour to feel safer, but these means are more expensive, such as private taxis.

This situation should be used to rebuild urban mobility by and for women, stressed Laura Pérez. To meet all these challenges, data is needed, and mobility must be designed to prioritise routes to reach markets, schools and hospitals. At the same time, it should generate perspectives of co-responsibility in which men are also responsible for carrying out these activities.

”The lack of data on women's mobility makes it difficult to measure what the impacts are for women in these measures, hence the importance of studies to present the issues and impacts that the pandemic has had on how we women move,” concluded the panellist.

Laura Pérez is a public policy analyst at C230 Consultores, with a focus on urban development, mobility and gender perspective. She is part of the Gender Mainstreaming and Social Inclusion team at Future Cities Mexico.

Mobility of Latin American women during the quarantine

For their part, Georgina Sticco and Alejandra Conconi presented preliminary data from research on women's mobility during quarantine in Colombia (Bogotá, Cali), Argentina (Buenos Aires), Mexico (Mexico City, Guadalajara), Peru (Lima), Ecuador (Quito), Chile (Santiago), Santo Domingo, Guatemala, El Salvador.

The study aimed to identify and make visible the problems related to access and quality in public transport for people who carry out essential paid and unpaid activities in the context of COVID-19, with a gender focus.

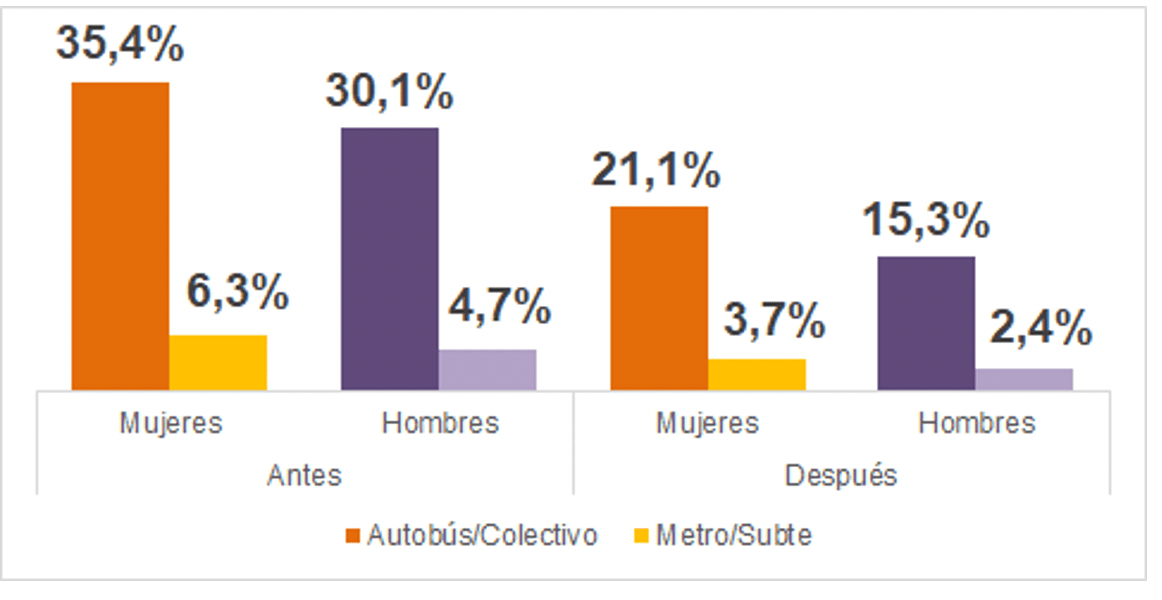

Generally speaking, it was confirmed that women have less access to private vehicles and use public transport more (from 60% to 66%), which exposes them to violence and harassment. The health crisis exposed and highlighted structural inequalities towards women in society.

This information aims to allow other types of definitions to be used in mobility planning for cities in the context of isolation or the gradual opening up of places from a gender perspective.

“We find that those who plan transport do not have this view and in this crisis situation it was not brought to the fore either. The urgency of making decisions meant that there was no thought as to how this would affect women in particular,” Georgina said.

In terms of methodology, online surveys and in-depth interviews were conducted with key women workers and public officials. In turn, a month-long ethnography of networks and exchange was generated with the participation of key informants. There was a total of 3,751 responses with 66% of women participating.

Among other results, increases of almost $3 dollars in the cost of travel were found in San Salvador, Quito and Buenos Aires. This was due, among other causes, to the increase in the price of informal transport, which is not regulated.

The final results of the study will present an analysis of the gender-disaggregated use of different types of transport: private vehicle, bicycle, public transport.

A slight increase in bicycle use was found. Women's reasons for not using bikes are long distances and lack of confidence, as well as the geography of the city. In all cases it is men who use bicycles more than women".

As for the cases witnessed in an intersectional manner, an increase in precariousness was reported, where the most notorious element was social class. Such is the case of the forced migration of women from Venezuela to Quito, the conditions of sex workers in San Salvador, birth assistants and indigenous midwives in Guatemala.

Georgina Sticco is co-founder and director of GROW, Gender and Work. Alejandra Conconi is an anthropologist specialising in diversity and inclusion in the world of work.

Here you will find the video of the webinar:

About EUROCLIMA+

EUROCLIMA+ is a programme financed by the European Union to promote environmentally sustainable and climate-resilient development in 18 Latin American countries, particularly for the benefit of the most vulnerable populations. The Programme is implemented under the synergistic work of seven agencies: the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID), the French Development Agency (AFD), the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Expertise France (EF), the International and Ibero-American Foundation for Administration and Public Policy (FIIAPP), the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ), and UN Environment.

For more information:

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

www.euroclimaplus.org